The Limits of GRPO-like Methods for Reinforcement Learning

The Weekly Kaitchup #118

Hi Everyone,

In this edition of The Weekly Kaitchup, I discuss:

The limits of current GRPO-like methods

The SYNTH/Bagettotron releases

Book Update

Everything is now bundled into a single 140-page PDF plus 9 companion notebooks. If you bought the book, you received it earlier this week.

Current chapters:

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

Prepare Your Training Dataset

LLM Quantization

Fine-Tuning Quantized LLMs

Efficient Inference with vLLM

One chapter is still in progress: LLM Evaluation. I’ll publish this chapter in December. Then, regular updates are planned in 2026 to keep the content relevant.

You can still grab the book at 30% off until November 30.

I read this very interesting paper on the limits of current RLVR-like methods (GRPO, GSPO, etc.) used to post-train LLMs:

Does Reinforcement Learning Really Incentivize Reasoning Capacity in LLMs Beyond the Base Model?

RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards) has been credited for recent “reasoning LLMs,” but this work shows it mostly sharpens sampling efficiency rather than expanding a model’s underlying reasoning capacity.

Something often underestimated with LLMs: The Sampling Effect

LLM outputs can vary a lot under stochastic decoding (temperature, top-p, etc.). We explored these effects on a quantized model, here:

Benchmark scores you read in papers, especially on hard sets, often reflect average accuracy. Run an AIME25 prompt 100 times and you may see ten-plus distinct answers. That’s where LLMs are today…

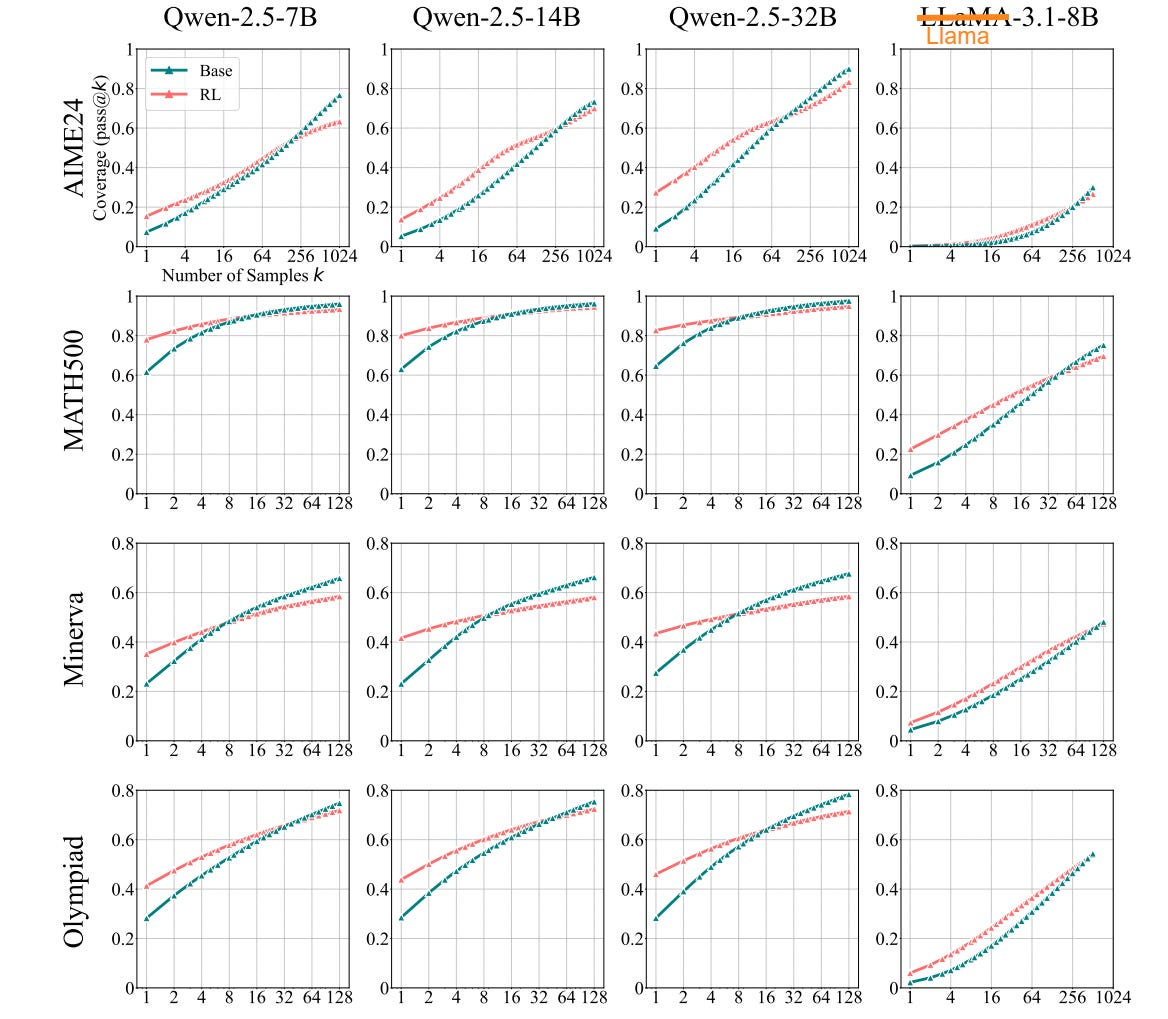

If you ran a lot of GRPO trainings, it’s probably something you already saw: RL-trained variants win when you can sample only a few outputs (small k, e.g., pass@1), yet the original base models overtake them as you allow more samples (large k, e.g., pass@128–1024). In other words, RL concentrates probability mass on already-rewarded trajectories without discovering fundamentally new reasoning paths. The authors did a large-scale study documenting this across coding, vision, and language tasks.

Put simply: if a model can’t already answer a question, GRPO probably won’t make it do so. Methods like GRPO mainly increase the chance of producing the correct answer. They don’t create new knowledge.

The key evidence is pass@k curves. If RL truly enlarged a model’s reasoning space, it should dominate base models even at high k, because “more draws” would expose more of its purported new capabilities. Instead, base models eventually match and surpass RL variants, implying that the RL model’s correct solutions already exist within the base model’s distribution. RL just makes those few “good paths” easier to hit with limited sampling while shrinking exploration elsewhere. This narrowing shows up as reduced diversity: rewarded trajectories are amplified, but the broader solution space contracts.

Their search-tree visualizations illustrate that all high-reward paths produced by RLVR are present in the base model. RL primarily reweights them. On some problems, this bias helps (higher pass@1), but on others it hurts (the RL model no longer samples the rare correct path the base could reach with broader exploration), producing worse pass@k at larger budgets.

Algorithmically, current RL variants, PPO, GRPO, Reinforce++, behave similarly. Measured by a “sampling efficiency gap” (∆SE) to an optimal strategy, they all remain far from ideal.

By contrast, distillation is positioned as fundamentally different: it can inject new knowledge and genuinely expand the set of solvable problems, whereas RLVR optimizes within the base model’s ceiling.

The authors pre-empt common critiques of pass@k. They emphasize they use it to probe capacity boundaries, not to claim practical deployment metrics. Even where guessing could be a concern (e.g., AIME, since the correct answer is always a number between 0 and 999), manual CoT inspection and coding benchmarks with strict unit tests show the same trend: base models retain broader problem coverage at high k. Thus, pass@k at scale reveals latent reasoning paths already present before RL.

Empirically, the study spans multiple families (e.g., Qwen2.5, Llama 3.1) and domains. This makes the work very convincing, and I guess that’s why the paper received the highest average score among all the NeurIPS 2025 submissions.

In math (GSM8K, MATH500, AIME24), RL lifts pass@1 but plateaus as k grows, while base models keep improving. In coding (LiveCodeBench, HumanEval+, MBPP+), CodeR1-Zero-Qwen2.5-7B gains at k=1 yet loses ground by k=128. For visual reasoning (MathVista, MathVision with non-MC filtering), the same pattern holds, suggesting the phenomenon is multimodal and not benchmark-specific.

A case study on hard AIME24 problems reinforces the point: with sufficiently large sampling (up to thousands), the base model finds correct chains of thought previously attributed to RL-trained systems. The base model’s long, reflective CoTs indicate robust latent reasoning that RLVR doesn’t create so much as re-prioritize, sometimes at the cost of excluding rare but correct solution paths.

I personally don’t like the current family of RLVR-like algorithms. They are brittle (choose the wrong data type and everything collapses) and slow. That’s why so many variants have been regularly proposed, trying to fix their many problems.

Nonetheless, the takeaway must be nuanced: RL is not “useless.”

It’s practically valuable for making single-shot or low-budget sampling stronger. But if the goal is to transcend the base model’s inherent reasoning boundary, RLVR methods as practiced today appear insufficient. Methods like distillation, or new training paradigms, are likely needed to truly expand capability.

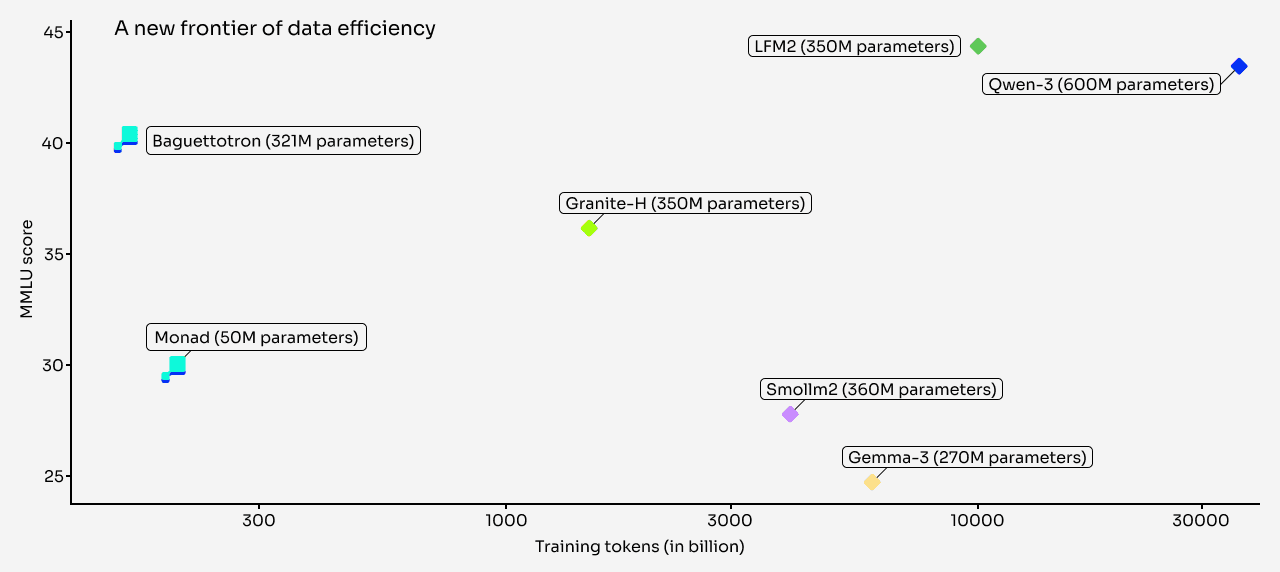

Baguettotron: A Very Deep Small Model

This is a very cool release by Pleias:

SYNTH is a fully generalist synthetic dataset designed to shift small models’ pretraining away from broad web crawls toward dense, reasoning-focused traces.

Seeded from 50,000 “vital” Wikipedia articles and expanded into diverse tasks (math, creative writing, information extraction, sourced synthesis), it aims to provide clean, connected reasoning paths rather than the noisy, isolated snippets typical of web data.

Instead of simple prompting, SYNTH is produced by multiple synthetic pipelines that integrate fine-tuned models, large-scale retrieval over structured Wikipedia, randomized constraints for diversity, and verification via formal checks or LLM-as-judge.

The generators often “know” the answer but simulate back-reasoning to produce stepwise traces, teaching small models to build answers rather than memorize them. Approximately 20% of the corpus is multilingual across major European languages; code is intentionally excluded for this release.

Trained on <200B tokens and <1,000 H100 hours for the final runs (≈20,000 H100 hours including generation/experiments; yes, the research phase always costs much more than training itself), two “deep” small reasoners: Baguettotron (321M, 80 layers) and Monad (56M, 64 layers). They achieve strong results, with Baguettotron reportedly best-in-class on MMLU, GSM8K, and HotPotQA.

These models are very deep and Llama-like, which makes them quantization-friendly. With a reasonable vocab size, unlike Gemma 3, where I had to slash the vocab, we can push them quite small via quantization.

You can get the models and dataset on the HF Hub:

The Salt

The Salt is my other newsletter that takes a more scientific approach. In The Salt, I primarily feature short reviews of recent papers (for free), detailed analyses of noteworthy publications, and articles centered on LLM evaluation.

This week, we review:

⭐Routing Manifold Alignment Improves Generalization of Mixture-of-Experts LLMs

Reasoning with Confidence: Efficient Verification of LLM Reasoning Steps via Uncertainty Heads

Too Good to be Bad: On the Failure of LLMs to Role-Play Villains

That’s all for this week.

If you like reading The Kaitchup, consider sharing it with friends and coworkers (there is a 20% discount for group subscriptions):

Have a nice weekend!