MiniMax M2 and Kimi-Linear: Why Full Attention Still Wins

The Weekly Kaitchup #116

Hi Everyone,

In this edition of The Weekly Kaitchup, let’s talk about linear/hybrid attention vs. full attention.

MiniMax just shipped an open-source, agent- and code-oriented model with about 10B parameters active out of roughly 230B.

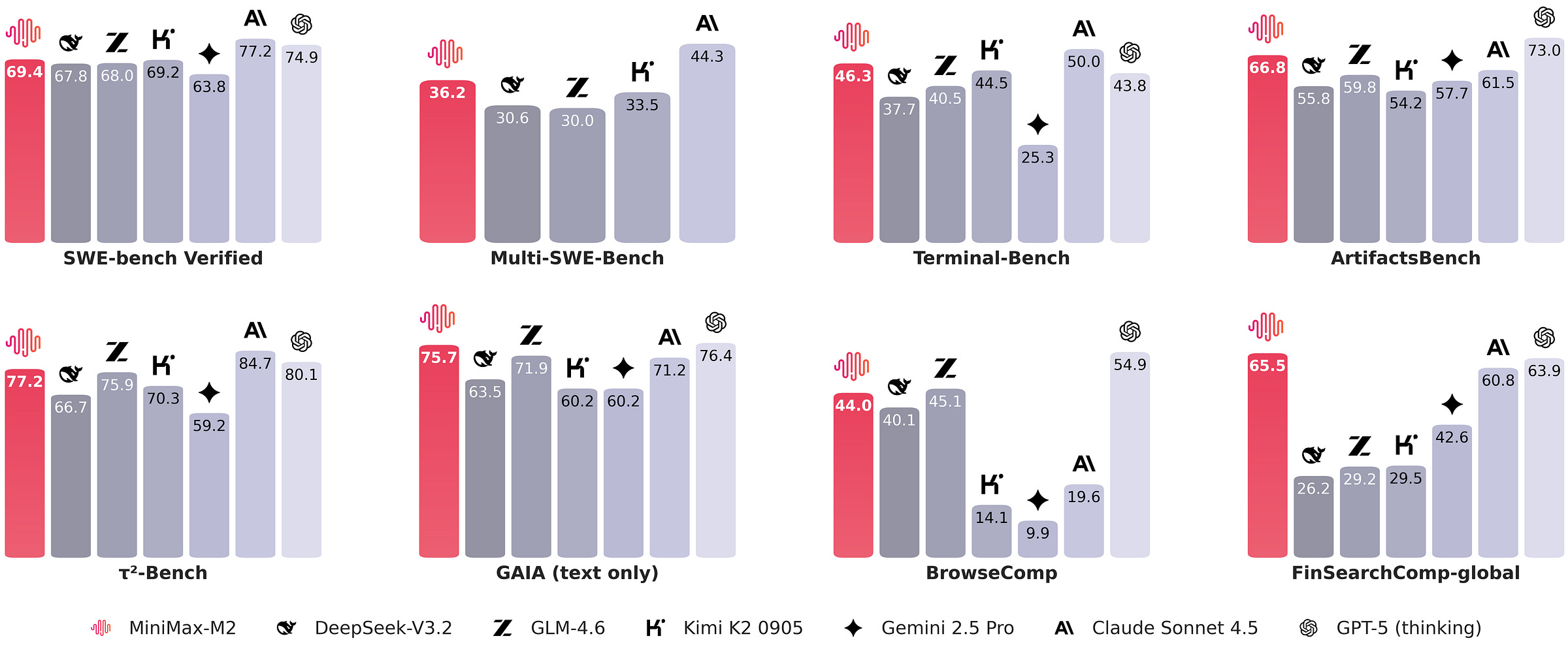

The model performs very well on benchmarks.

What I want to dig into is this: earlier MiniMax models aligned with the current trend toward hybrid attention (see Qwen3-Next, LFM, Granite 4.0, etc.), but with this release, they’ve gone back to plain full attention.

And they justify it pretty convincingly on X (original post in Chinese here).

Their core claim is: full attention still wins because it’s the least fragile choice across tasks, model sizes, and inference stacks. “Efficient” attention isn’t dead, it’s just not mature enough to be the default for a system that has to do code, math, agents, multimodality, long-chain reasoning, and RL on top. The problem isn’t the theory but rather the long list of conditions that all have to line up before an “efficient” design is actually efficient in production.

If your real objective is “same quality with fewer tokens,” scaling laws usually give you safer, more predictable gains than swapping out attention.

Hybrid attention looks good on public leaderboards, but MiniMax says it broke down on higher-order, multi-hop reasoning once they scaled the models. To even see that, they had to build new internal proxy metrics, and even those can drift as the model or data mixture changes.

Full attention, meanwhile, sits on years of kernel and inference engineering. Linear and sparse attention don’t. To reach the theoretical crossover point where they’re clearly better, you still need:

low-precision state that doesn’t nuke stability,

cache-friendly layouts that match real conversational traffic,

speculative decoding paths that work with nonstandard attention.

Until all of those land together, the speed/price gains get eaten by IO, precision quirks, or serving constraints.

But their most important point is about evaluation:

When you change a primitive like attention, you should assume public benchmarks will understate the damage. You need longer, richer, sometimes slower evals to surface regressions in reasoning, agentic behavior, and RL stability. Those evals are very expensive, but without them you can’t honestly claim the model is “efficient,” because whatever you lost will be repaid later as extra engineering, extra data, or extra compute. I 100% agree with that!

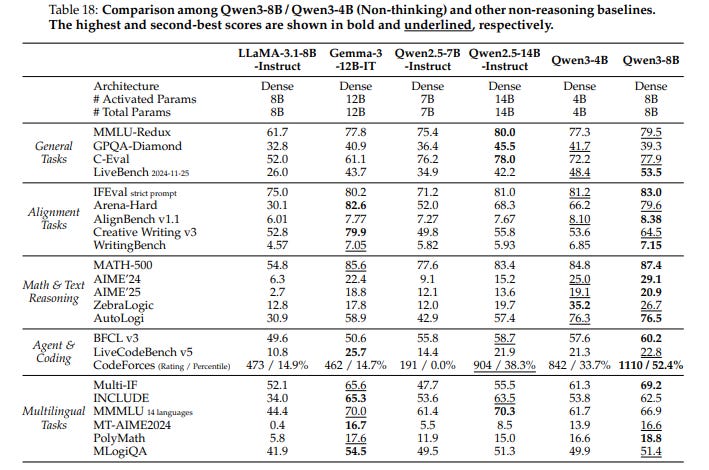

Qwen3-Next is a nice illustration. It’s an 80B model that does well on most public sets, but once you push it, it can fail hard and lose to a model ~3x smaller. My guess is that’s also why Qwen didn’t train it past ~15T tokens. The loss probably flattened, or worse, started to degrade at scale.

So my view is: we’re stuck with full attention as the default until we have an architecture that both scales and learns better. Just making inference cheaper (linear attention), or trying to stay close to full-attention quality (hybrid attention), isn’t enough.

I was going to just say that, but Moonshot AI just dropped a new model with linear attention and very bold claims:

Kimi Delta Attention: A hardware-efficient linear attention mechanism that refines the gated delta rule.

Kimi Linear Architecture: The first hybrid linear architecture to surpass pure full attention quality across the board.

Empirical Validation: Scaled, fair comparisons + open-sourced KDA kernels, vLLM integration, and checkpoints.

A linear-attention architecture that actually beats full attention, and already ships with specialized kernels inside one of the most used inference stacks (vLLM), is almost the exact opposite of MiniMax’s argument.

So let’s look closer.

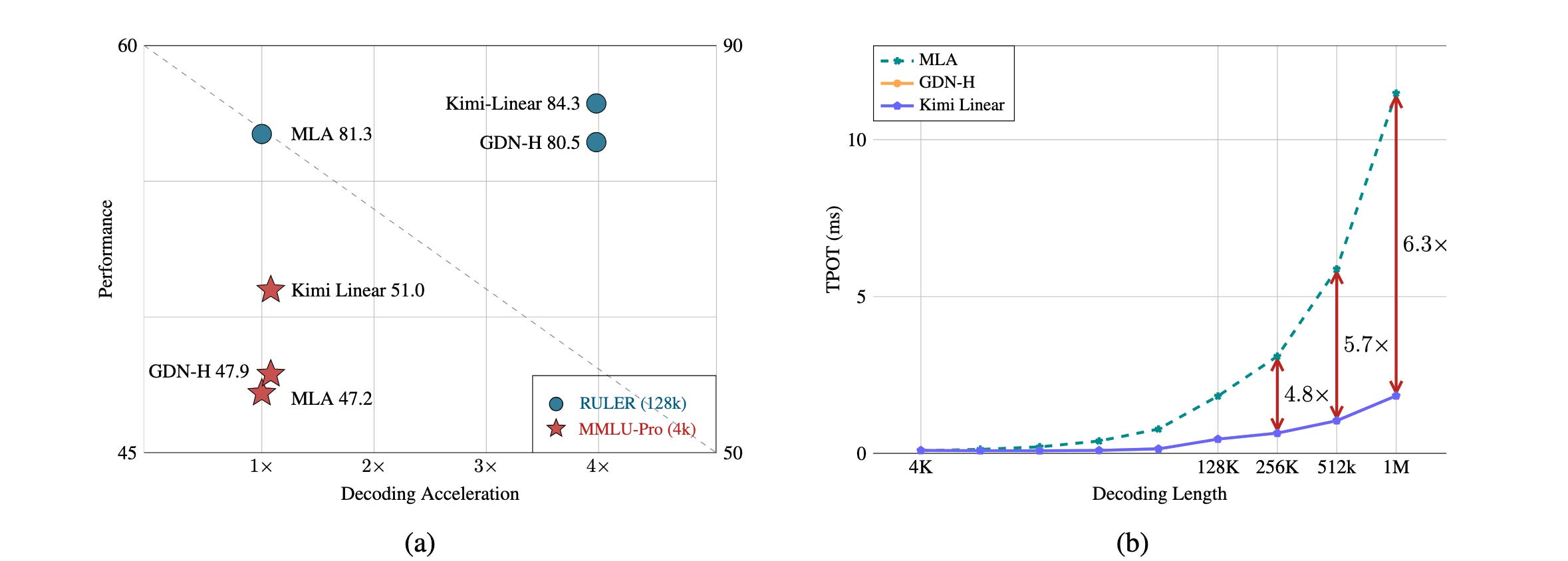

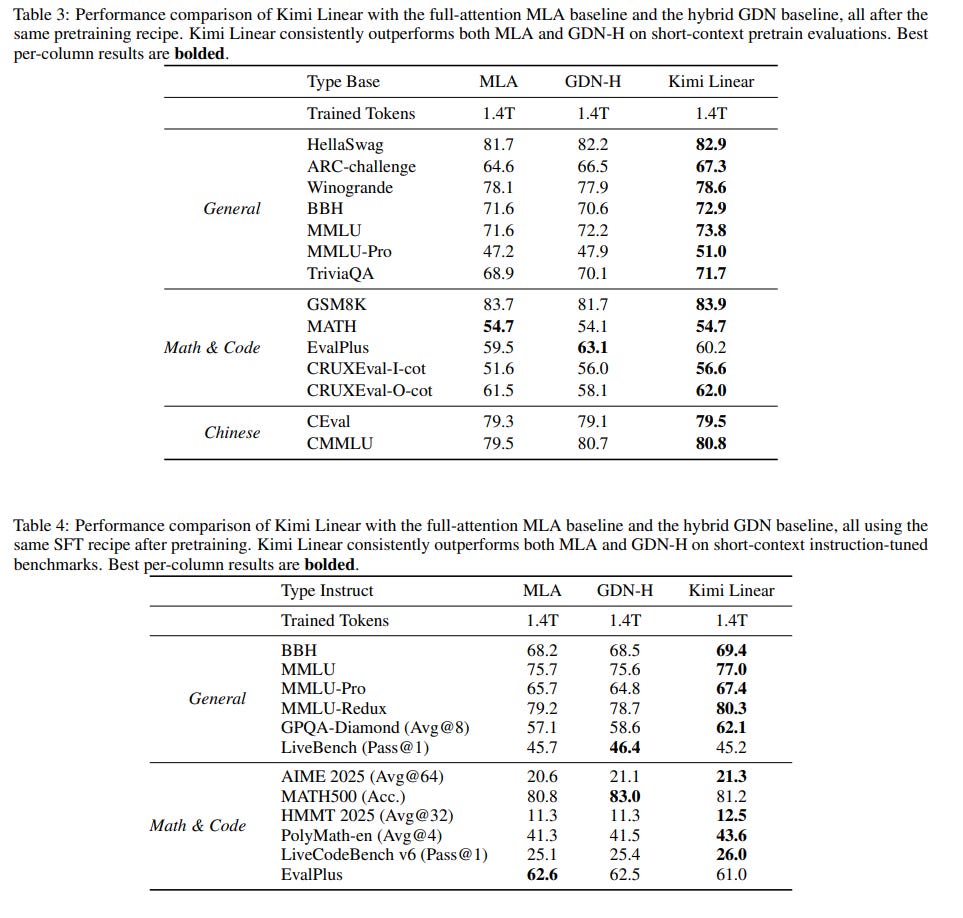

In Moonshot AI’s own report, they claim that Kimi Linear outperforms the same model trained with multi-head latent attention (MLA) and with the original gated delta-net (GDN, basically the “linear” flavor Qwen3-Next used).

These results are encouraging, but saying Kimi Linear beats full attention is overstated. If you read the tech report, you actually rediscover most of the issues MiniMax raised:

Scale: all comparisons are at ~1.4T training tokens. That’s well below the regime where fragility usually shows up.

Baselines: there’s no plain, well-tuned full-attention baseline. MLA is strong but not mainstream, and GDN isn’t full attention at all, so it’s hard to call this a clean win.

Absolute scores look low: I know we shouldn’t compare numbers published by different labs, but just to get an order of magnitude, many of their reported scores are below what Qwen3-8B, or even Qwen3-4B (non-thinking), delivers. So “better than full attention” here really means “better than the particular efficient-attention setups they tried.”

This isn’t very convincing for a 48B model. Results at 1.4T tokens just aren’t enough to support the claims Moonshot AI is making, especially since they didn’t publish the scores for the checkpoint they actually released (the 5.7T-token one), neither in the report nor in the model card (they are/will be probably somewhere).

If we drop the “better than full attention” framing and look at it for what it is, though, Kimi Linear is a good model that makes long-context workloads much cheaper.

It reduces the need for large KV caches by up to 75% and boosts decoding throughput by up to 6x for contexts as long as 1M tokens.

More releases this week:

IBM also just released new Hybrid Attention Granite 4.0:

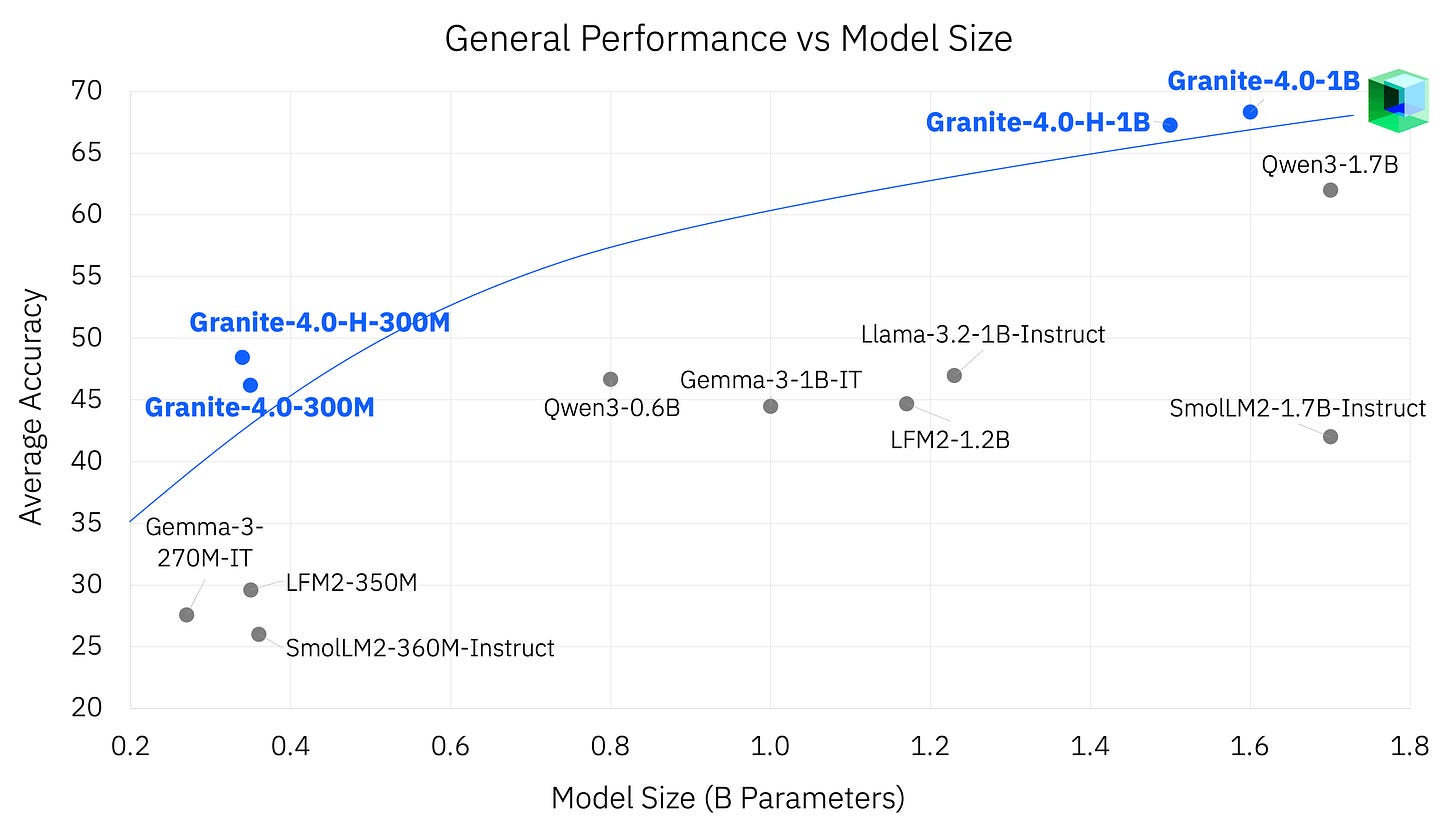

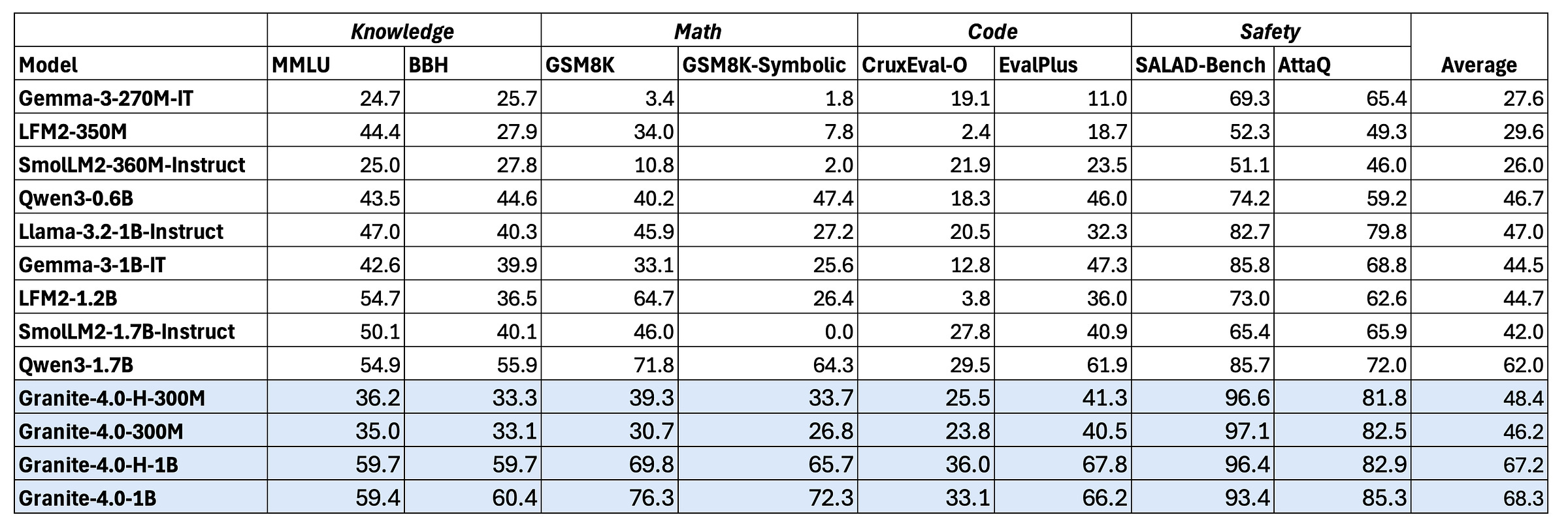

There are 1B and 350M models. The performance looks OK overall:

Note: This is an “average” accuracy, which is often skewed by a few benchmarks, i.e., that’s much less informative than per-benchmark accuracy and shouldn’t be seen as showing that a model is better than others.

I later found they actually averaged the scores of an unusual selection of old benchmarks:

Third-party evaluation with more standard benchmarks by Artificial Analysis shows the models may underperform Qwen3 but is better than LFM2.

More details here: Granite 4.0 Nano: Just how small can you go?

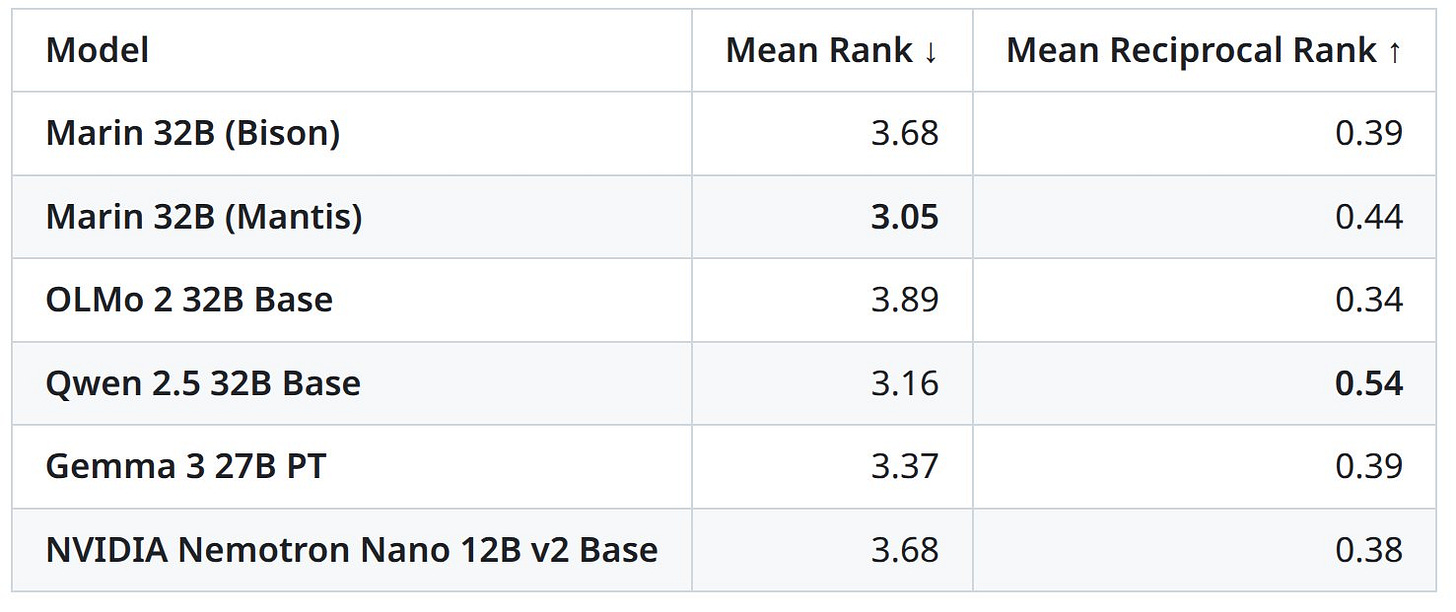

Marin 32B also finished training this week. It’s a genuinely open-source model, like OLMo, trained by the Marin community. Percy Liang even announced it as the best open-source base model so far.

They report results using Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), Percy has been pushing MRR over naïvely averaging benchmark scores, and I agree it’s a better signal, even if it’s not perfect:

The full report is a great illustration of how hard it is to train a base model from scratch: failures, bugs, restarts, and a few “this is bad but we can’t explain it so we’re shipping anyway.” Definitely worth reading:

The Salt

The Salt is my other newsletter that takes a more scientific approach. In The Salt, I primarily feature short reviews of recent papers (for free), detailed analyses of noteworthy publications, and articles centered on LLM evaluation.

This week, we review:

⭐Reasoning with Sampling: Your Base Model is Smarter Than You Think

BAPO: Stabilizing Off-Policy Reinforcement Learning for LLMs via Balanced Policy Optimization with Adaptive Clipping

Knocking-Heads Attention

That’s all for this week.

If you like reading The Kaitchup, consider sharing it with friends and coworkers (there is a 20% discount for group subscriptions):

Have a nice weekend!